Living with Ghosts | Pace Gallery, London

The second iteration of Living with Ghosts was held at Pace Gallery, London, from July 8 - August 5, 2022.

Living With Ghosts is an expanded iteration of Abudu’s ongoing exhibition project, first staged at the Wallach Art Gallery at Columbia University in New York. Each of the artists included in the exhibition are united by their formal, historiographic, and poetic interrogations of the enduring power structures birthed by the transatlantic slave trade, colonialism, and imperialism, and equally consider the myriad resistances and refusals formed in response to these very structures. Living With Ghosts at once evokes the structural continuities of these African colonial histories into the present day, while also offering a transformative space for envisioning alternative and more just decolonial futures.

Spanning a diverse array of media, from video and installation to works on paper and sculpture, Living With Ghosts features work by Mathieu Kleyebe Abonnenc, Dineo Seshee Bopape, Nolan Oswald Dennis, Torkwase Dyson, Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Bouchra Khalili, Abraham Oghobase, Cameron Rowland, and Tako Taal. Taking inspiration from Achille Mbembe’s theorising on the African “postcolony,” Jacques Derrida’s notion of “hauntology,” and Sylvia Wynter’s work on the “coloniality of being,” Living with Ghosts critically attends to the ghosts, spirits, and phantoms that abound in the modern calamities of Africa’s historical becoming, from the 15th century to the present day.

These “ghosts” are the unseen but deeply felt forces – at once dead and alive, visible and invisible, past and present, future and past – that continually disturb individual and collective relations within the African postcolony and throughout the world, leaving behind traces in archival materials, architecture, landscapes, and subjectivities. Heeding Derrida’s provocation in Specters of Marx (1994), as well as insights from various African indigenous thought systems, this exhibition foregrounds the ethical and political urgency of feeding, communing, and living with these ghosts rather than disavowing, burying, or exorcising them.

By centering contemporary art practice in spectral considerations of violent pasts that continue to linger and of liberatory futures that continue to haunt, Abudu frames the exhibition’s concepts along several axes, from the spatial and the temporal, to the psychological and the spiritual.

Living With Ghosts also includes a lecture series and a reader publication (more below), both of which provide complementary critical perspectives on the exhibition’s overarching concerns with coloniality, decoloniality, and hauntology.

ACT I

The gallery display included works by Mathieu Kleyebe Abonnenc, Dineo Seshee Bopape, Nolan Oswald Dennis, Torkwase Dyson, Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Bouchra Khalili, Abraham Oghobase, Cameron Rowland, and Tako Taal.

The accompanying curatorial essay for this act can be found here. Below is a short excerpt:

“While the artworks presented in these galleries evidence distinct methodologies, sensibilities, and art historical genealogies, they all share an ethical and political commitment aimed towards inciting an anticolonial politics of memory. By working with and through unresolved pasts and elapsed futures, these artworks gather and in turn release specters in the world, with the hope that these specters haunt those that encounter them. In being haunted, we are forced to acknowledge the absent-presences of ghosts in everyday life. Such an acknowledgment –speaking of, speaking to, and living with these ghosts – inaugurates a crucial movement away from the blinded comforts of historical amnesia and orients us toward the possibility of truly reckoning with “past” colonial injustices (many of which are committed in seemingly far-away places) and the ways in which these injustices continually structure our present. Further, in being haunted through our affective encounters with these ghosts, we are opened up to the possibility of being possessed by the desirous visions they convey, of just, decolonial futures that were never realized and which we are now tasked with the responsibility of bringing about.”

Checklist:

Mathieu Kleyebe Abonnenc

Foreword to Guns for Banta, 2011

Mixed Media: Synchronised slide show transferred to HD, 25 minutes, 40 seconds; Poster, 120 cm × 160 cm

Courtesy of the artist

Dineo Seshee Bopape

Lerole: footnotes (the struggle of memory against forgetting), 2018

Mixed media

Variable dimensions

Courtesy of the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery

Nolan Oswald Dennis

biko.cabral (time/place), 2020

Thermal printer, microcontroller, shelf

Variable dimensions

Courtesy of the artist and Goodman Gallery

Torkwase Dyson

Black World Building, (Hypershape), 2022

Wood, graphite, acrylic

111.8 cm × 112.4 cm × 3.8 cm

Courtesy of the artist and Pace Gallery

Torkwase Dyson

Symbolic Geography #1 (Hypershape), 2022

Wood, graphite, acrylic, glass

49.5 cm × 58.4 cm × 8.9 cm

Courtesy of the artist and Pace Gallery

Torkwase Dyson

Enclosure/Encounter – Study #4 (Hypershape), 2022

Graphite and pen on paper

29.2 cm × 41.9 cm

Courtesy of the artist and Pace Gallery

Torkwase Dyson

Enclosure/Encounter – Study #5 (Hypershape), 2022

Graphite and pen on paper

29.2 cm × 41.9 cm

Courtesy of the artist and Pace Gallery

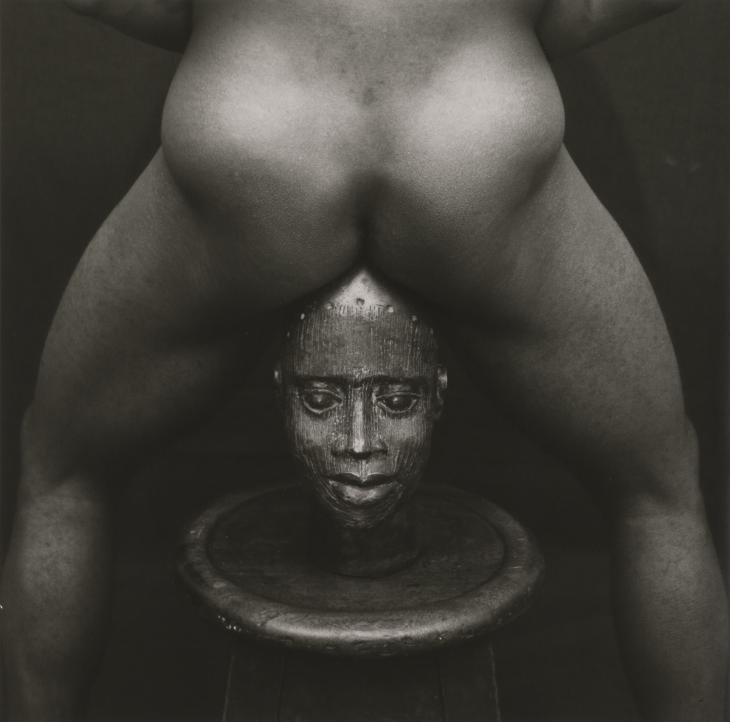

Rotimi Fani-Kayode

Sonponnoi, 1987

Hand printed gelatin-silver print from the original negative

61 x 50.8 cm

Courtesy of The Walther Collection and Autograph ABP, London

Rotimi Fani-Kayode

Under the Surplice, 1989

Hand printed gelatin-silver print from the original negative

61 x 50.8 cm

Courtesy of The Walther Collection and Autograph ABP, London

Rotimi Fani-Kayode

Nothing to Lose VII (Bodies of Experience), 1989/2021

C-type archival print

121.9 cm × 121.9 cm

Courtesy of Hales Gallery, London and New York; and Autograph, London

Rotimi Fani-Kayode

Nothing to Lose IX (Bodies of Experience), 1989/2021

C-type archival print

121.9 cm × 121.9 cm

Courtesy of Hales Gallery, London and New York; and Autograph, London

Bouchra Khalili

Foreign Office, 2015

Mixed media: single-channel digital film, 22 minutes, 6 seconds; 15 digital prints on paper; silkscreen print on paper

Courtesy of the artist and Mor Charpentier, Paris

Abraham Oghobase

Constructed Realities, 2022

Wood, inkjet on fibre paper, inkjet on silk organza

130.6 cm x 373.5 cm x 226 cm (depth variable)

Courtesy of the artist

Tako Taal

I fa mo ketta (It’s been a long time), 2017

HD Video, no sound

9 minutes, 27 seconds

Courtesy of the artist

Tako Taal

Absence/Baduja (the state of being away, the condition of being related), 2021

Watercolour on paper, imitation leather, gold chain, seashell

34 cm × 34 cm × 3.5 cm

Courtesy of the artist

Cameron Rowland

Mooring, 2020

AB-001-013

William Rathbone and Sons was a timber merchant company founded in Liverpool in 1746. “[T]he foundation of the Rathbone fortune and business was built on the Africa slave trade.”[1] During the 18th century, they imported timber felled and milled by slaves in the West Indies and operated a number of trading ships that sailed to West Indian colonies as well as the Southern States of America.[2] Rathbone and Sons’ yard occupied a large portion of the Liverpool South Docks.[3] Rathbone and Sons supplied timber for slave ship builders in Liverpool until at least 1783.[4] These ships carried enslaved black people who were sold in the West Indies and in British North America. Ships built in Liverpool also carried the slaves who were sold on Negro Row at the Liverpool South Docks.[5]

Liverpool built the world’s first wet dock in 1716, allowing cargo ships to dock directly at the port. By 1796, Liverpool had built 28 acres of docks.

Liverpool’s proximity to Ireland also not only facilitated a profitable trade, but provided a relatively safer route that allowed Liverpool ships less chance to be captured by French privateers. Additionally, the copper and brass manufactures in Lancashire and Ireland allowed for local companies that manufactured African trade goods such as manillas to carry on a prosperous export trade, further giving Liverpool a competitive edge. The relationships forged with nearby merchants not only helped secure trade goods, but also valuable credit terms.[6]

In 1784, Rathbone and Sons imported the first consignment of raw cotton to England from the United States.[7] From this point, they became stated abolitionists and free trade advocates.[8] The abolition of the “West Indian monopoly” on the import of goods to the British Isles would allow for the expansion of U.S. cotton trading. Liverpool became the primary port of 19th-century cotton importation to England. Rathbone and Sons imported American cotton to Liverpool through the American Civil War.[9] The company continues to operate as the investment and wealth management firm Rathbone Brothers Plc.

The mooring at the Albert Dock: AB-001-013 is on the former location of the Rathbone warehouse.

This mooring has been rented for the purpose of not being used. It continues to be rented for this purpose indefinitely.

Courtesy of the artist and Maxwell Graham/Essex Street, New York

[1] Jehanne Wake, Kleinwort Benson: The History of Two Families in Banking (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 15.

[2] Wake, 16.

[3] Adam Bowett, “The Jamaica Trade: Gillow and the Use of Mahogany in the Eighteenth Century,” Regional Furniture 12 (1998): 22.

[4] Wake, 16.

[5] Eric Williams, Capitalism and Slavery, 2nd ed. (1944; repr. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1994), 52.

[6] Katie McDade, “Liverpool Slave Merchant Entrepreneurial Networks, 1725–1807,” Business History 53, no. 7 (2011): 1094.

[7] Eleanor F. Rathbone, William Rathbone: A Memoir (London: Macmillan and Co. Limited, 1905), 11.

[8] Wake, 15, 31.

[9] Sheila Marriner, “Rathbones’ Trading Activities in the Middle of the Nineteenth Century,” Transactions of the Historic Society of Lancashire & Cheshire 108 (1956): 118.

ACT II

The second act consisted of three lectures:

An outdoor sonic lecture by Hannah Catherine Jones in Hannover Square

A virtual lecture by Sabelo J. Ndlovu Gatsheni, “Colonialism and its Afterlives”

A performance video-lecture by manuel arturo abreu

ACT III

The third act is the publication, Living with Ghosts: A Reader.

The reader, as the exhibition’s residual afterlife, further expands on the exhibition’s thematics through a combination of philosophical, historical, and literary approaches. Included are reprinted texts by thinkers such as Achille Mbembe, Avery F. Gordon, C.L.R. James, Jacques Derrida, Walter D. Mignolo, and Sabelo J. Ndlovu-Gatsheni as well as newly commissioned texts by Adjoa Armah, Joshua Segun-Lean, Emmanuel Iduma (on the work of Abraham Oghobase), and myself (on the work of Black Audio Film Collective and John Akomfrah). Also featured is an in-depth conversation between artist Bouchra Khalili and myself.

The introduction to the reader can be viewed here.